Where did you grow up? I grew up in Colorado Springs, Colorado. My dad taught physics at Colorado College and my mom taught Gifted and Talented at an elementary school. They took summers off so we would take a lot of outdoor trips, hiking the 14,000 foot mountains and canoeing, and going to the National parks. They did a lot of adventuring with my older brother and me when we were young.

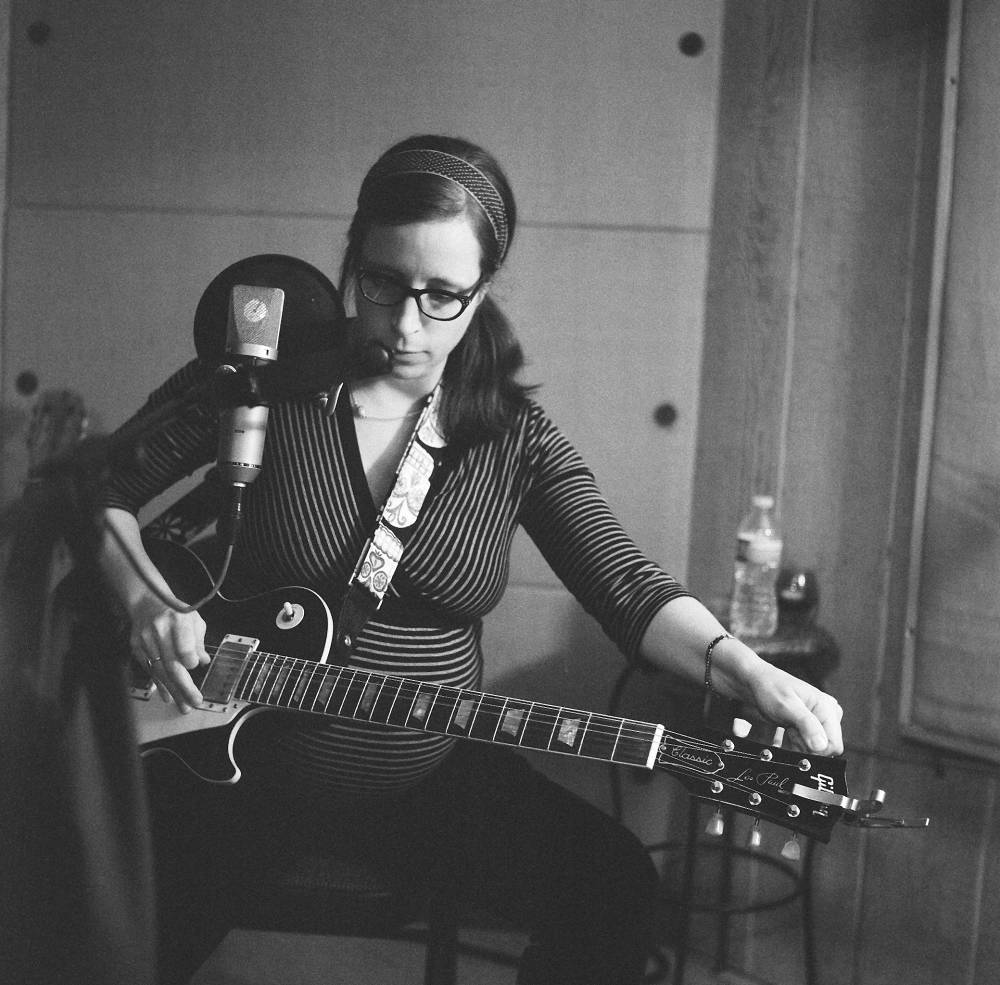

When did you start making music? I was 19 when I first got serious about music. I went to college at Carleton College in Minnesota and studied geology, but I got involved with the indie-rock/punk underground scene. I started an all girl punk band and started writing a lot of songs around that time. I remember when I first started writing I knew it was my thing. I just loved writing songs.

So writing music came pretty easy for you? Yeah. Really easy. Now it’s hard, because I’ve done it for 20 years, but early on it was just so fun. I just remember it being like a puzzle, like problem solving.

“I remember when I first started writing I knew it was my thing.”

How did you learn to play guitar? I taught myself at first, and my brother had shown me some chords when I was 18. Then when I moved to Seattle after college I found a great teacher who taught me fingerstyle country blues, and that really informed the way that I still play. I play mostly nylon string guitar, fingerstyle, but I also play electric and acoustic, banjo, and a little piano.

There’s something really powerful about being self taught that I admire in musicians. My work is very much from the do-it-yourself kind of ethic of the riot grrrls, that kind of—Ani Difranco driving around in your car selling tapes from the back. That kind of thing really informed the approach that I take. Did you learn from a young age?

Yeah. I started piano lessons when I was eight, and started flute in my school band program which led to private lessons in flute, and went on to study it in college. I finished up with earning my Master’s degree in Flute Performance. Studying music in school is heavily based on technique and theory and history, and it’s very academic, and sometimes it can be easy to forget about the passion that made you love it in the first place. I look at my niece who is 14, and she’s a really talented singer, but she’s never had any lessons. And every time I hear her sing I just start crying because it’s coming from inside of her, and nobody has messed with that yet. It’s such a powerful thing. It’s really cool when someone can discover that on their own, and it’s also really cool when someone gets guided. I honestly feel a little conflicted with that with my kids, because I wasn’t taught music. And I tried to get my son into some piano lessons and he just didn’t like it. He’s seven, and the other one’s four, and I was like, you know, I can’t tiger mom this. I can’t. If he wants to get into music, we can totally get him drum lessons if he wants, or whatever. But right now he’s into art and reading, so just let it be. They hear music all the time at our house, so they can find it their own way. I do know some musicians who are classically trained and also wonderful improvisors and creators, and I kind of envy them, because they have it all. They have the theory, they have the reading and the technique, but they also have the spirit of creativity. And that’s just rare, honestly.

When did you decide to become a mom? For a long time I was very ambivalent, because I thought being a parent wouldn’t fit with being a touring musician. I would tour for four months out of the year for years. Then when I was 31, that funky, powerful, biological clock kicked in: Must have children. Now. I wasn’t married to Tucker (my husband) at the time, but we talked about it and he was honestly more realistic. He was like, this is going to be really hard.

He’s a producer. He works on making records for bands and manages his own studio. He records all of my music and also works with other bands like My Morning Jacket, a lot of jazz bands, every style of music. He sometimes works really long hours with an unpredictable schedule, and unpredictable pay. It’s just not exactly what you think of when you’re thinking of becoming a parent. He was a little more realistic than I was about what we were up against. I was like, it’ll be fine!

And it is fine, but it’s definitely challenging. He had more mentors, close friends who were parents in the business, who he had seen struggle. He knew it was going to be really hard, but we went for it. We had a miscarriage the first time. I think I was 35 or 34, because I had my first child when I was 36 and my second when I was 39. By that time I had really established myself as a songwriter with my own catalog, owning my own music, my own label. Having done seven or eight records, I knew that I could relax a little bit financially. I could justify taking six weeks off, which is not much for a new parent.

I wanted to get back to work, and six weeks out I was working four hours a day. I’d have a babysitter come, I would nurse the baby and the babysitter would take him. At the time I had a studio in the backyard where I could work. The first year I didn’t really want to write because I was so exhausted, so I did an album for children. My husband and I researched the folk history of American and English folk songs, and I collected those and made Tumblebee.

It was nice because I could take a break from writing, but I could still have my identity and be creative. It gave me a platform to tour, as I did when both kids were babies. I also toured for four months of my first pregnancy, through very frozen lands in the winter in Sweden and Norway.

How was that? It was really hard work. I was exhausted, and I was afraid I was going to fall on the ice. My husband wasn’t there, so I was out on the road with my band. Then once we had the kids, we did take them on tour. Now that they’re older I’m trying to figure that out.

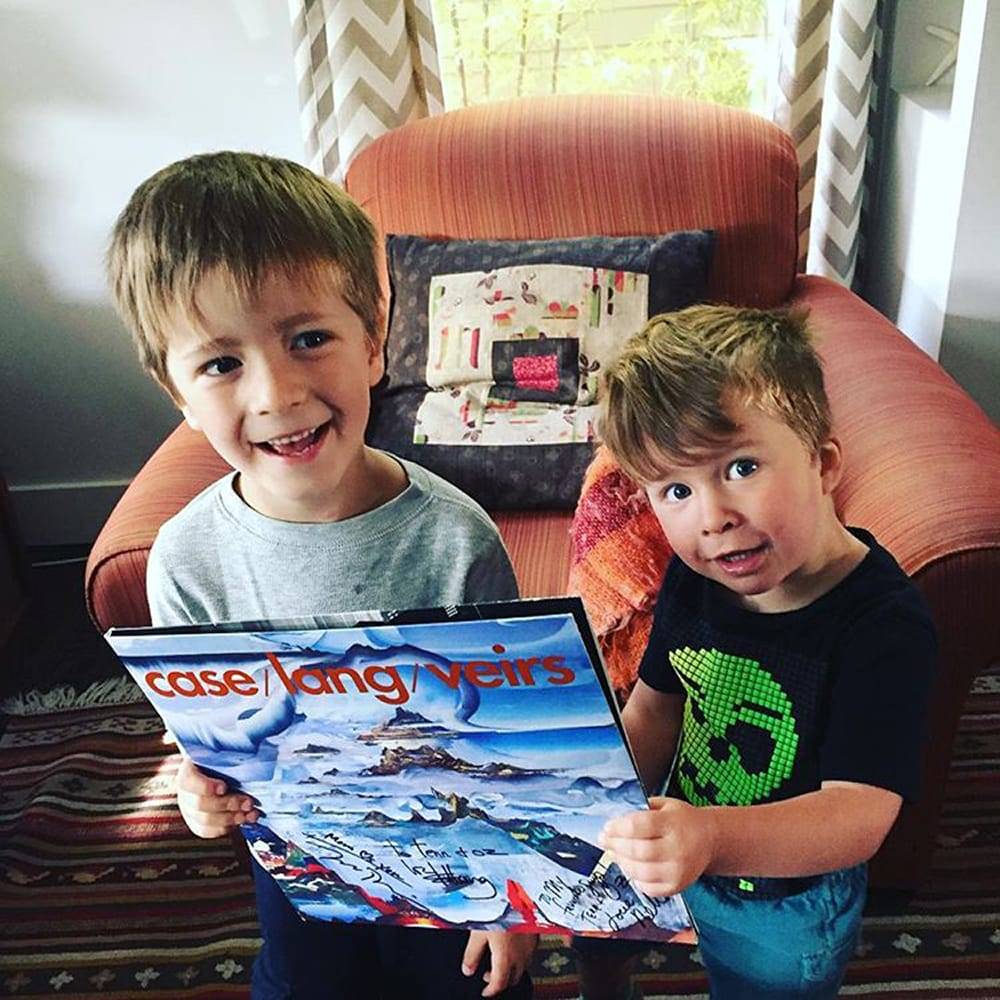

I released an album last summer with k.d. lang and Neko Case, a collaborative project with the three of us writing songs together. It wasn’t going to make sense to bring the kids on that tour, so I was gone for seven weeks. It was hard, and it was also hard on Tucker. He had help, with summer camps and babysitters. It was three weeks on, one week off, and four more weeks. At the end of those four weeks I had felt it was too long, but they were fine. They did great. It was just a blip on the screen, no big deal really.

How was it when they were babies, taking them on tour? I got the advice to do that, and I was really grateful. Before you have a kid you don’t realize how portable babies are. In a way, it’s hard. You’re tired. You’re not sleeping that well. I would be with him most of the day. At certain venues my parents were there watching him while my husband was drumming in the band, or we had a nanny.

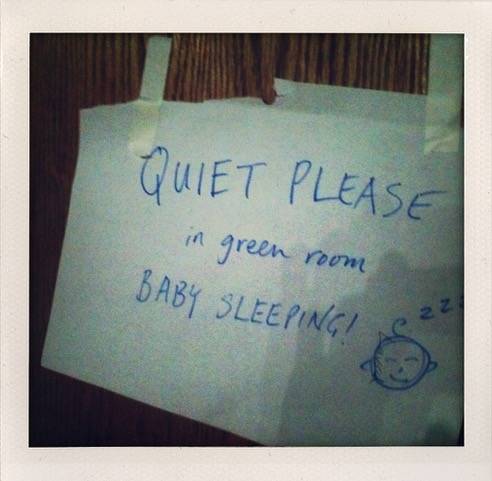

“Sometimes we put them to sleep in a side room, or a closet, or under a sound board. We put them to sleep in the weirdest places!”

Sometimes we put them to sleep in a side room, or a closet, or under a sound board. We put them to sleep in the weirdest places! Sometimes we would put them to sleep under the seat in front of us in airplanes, which sounds weird, but it was a relief! You’re holding a baby for five hours, and it’s tiring! It doesn’t look tiring, because you just see a person holding a baby. But it’s actually hard work. We’d swaddle the baby, nurse him, and put him to sleep underneath the seat in front of us, and take a break.

I remember at the end of one of those tours, we had to play a gig in North Hampton, and then I had to catch a flight out of Boston three hours later. It was the kind of thing where I had had three hours of sleep, and I didn’t have a babysitter with me. I was by myself with this baby, flying back to Portland from Boston, and I was exhausted from the tour, running on just three hours of sleep. So, I tried my trick of putting him to sleep underneath the seat in front of me and it totally wasn’t working. It just looked really bad. People were looking at me like, “What’s her problem? Why can’t she just hold her baby?” And this lady next to me said, “Can I hold your baby?” And I was like, “Yeah! Here!” And I handed him over and took a nap, because I was so tired. I could not hold him! She had a friend there, and the friend held him too. Talk about a village. That’s like a village of strangers.

How have your kids shown up in your music? There’s a song called “Sun Song.” It’s about spring, and the sun. The sun is elusive in the Northwest, and the rain is unrelenting sometimes during the winter. It’s about that, and about my boys being a solace for me.

I have written other songs about them, but it’s a tricky thing because it’s hard to articulate the feelings a mother has for her child. I don’t always do it successfully. But they make their way in there. They are on my new record, which is coming out in April. It’s a song called “When it Grows Darkest.” It’s a song about teaching children peace and love. There’s also a song called “Watch Fire,” which is about protection. I’ve got to protect them. I’ve got to keep the watch fire burning.

Do you see the fact that you’re a musician influencing how your kids see you as a role model? Yes. My husband and I are both in the arts, and I think our kids can see how important music is to us. I think they respect us and look up to us, but most children do that for their parents no matter what. And they humble us.

The other day, I went down to L.A. to interview Carole Kaye who is a bass player and literally played on ten thousand recording sessions in the 60s and 70s. I really admire her, and she’s been a mentor to me. I wrote a song about her. I asked my older son, “Do you want to know who I’m going to talk to in L.A. today?” And he’s like, “I don’t care.” I was like, ok, whatever, she’s just one of the best bass players ever.

“Every parent has to have the walk of shame out of the restaurant when the child is screaming and writhing in their arms. It’s just part of the deal.”

And I wrote this book for kids called “Libba,” about Elizabeth Cotten, who was a woman musician of the folk era, and she was discovered by the Seger family in the 60s. She’s also been a huge influence on me, guitar-wise. Her story is awesome. The book is beautifully illustrated by Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, and she just nailed it. And the other day, my son was like, “Your book is boring. It’s just boring”. Ok. That’s humbling.

I think that is a good thing for artists, too, because sometimes we can be a little self important. It’s partially what drives us to create: that feeling that we have something to offer. But taken too far it becomes narcissistic, and children are great buffers for that. Every parent has to have the walk of shame out of the restaurant when the child is screaming and writhing in their arms. It’s just part of the deal.

It’s just humbling. And the sleep deprivation is humbling. The demand on your time and energy is humbling. As long as it doesn’t grind you down to a nub and you have nothing left to give, it can be a good thing for artists.

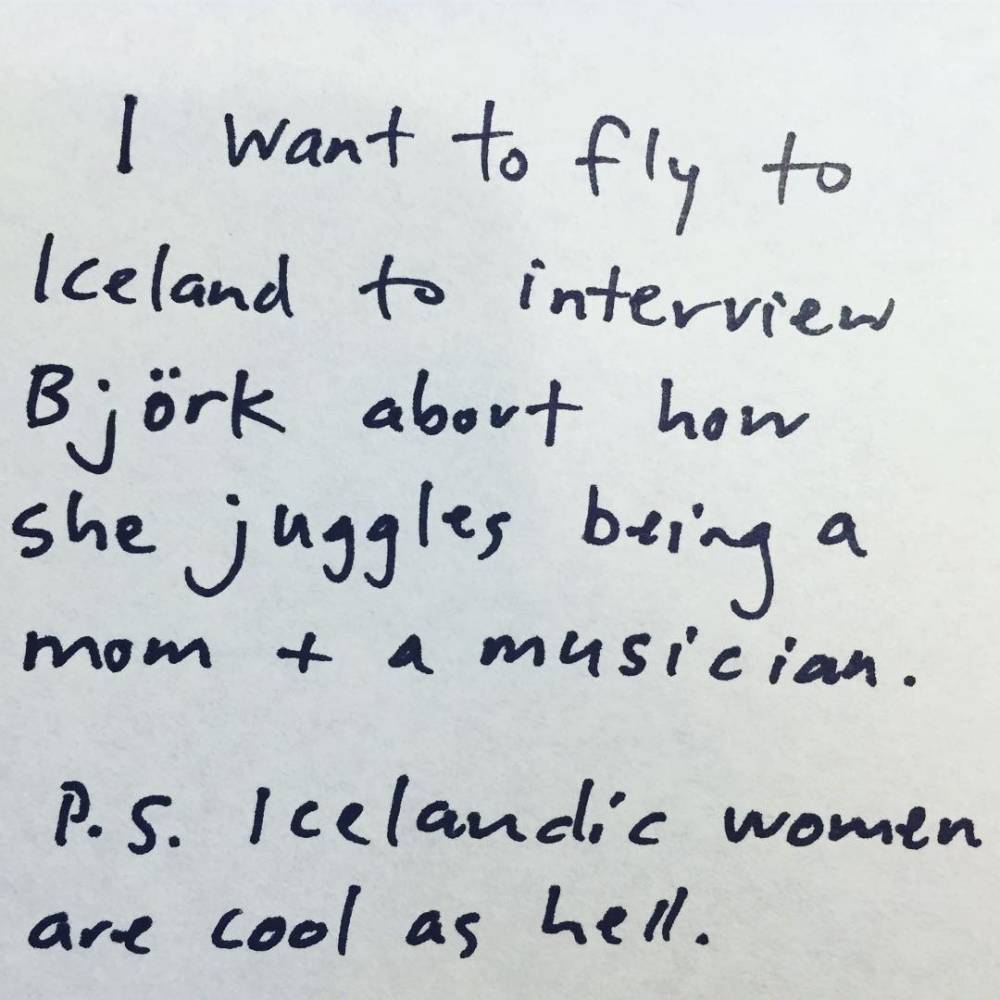

You recently made a post on social media saying you wanted to go to Iceland and interview Bjork about motherhood. What is it about Bjork that you find intriguing? Well, she’s interesting to me because she had a child very young, and then she had a child very old. She split it up that way and I’m not sure why. I am also interested in Icelandic women after watching the Michael Moore documentary “Where to Invade Next,” where he went to different countries to show the great ways that they ran their education system, or food systems, for example, demonstrating that some of these ideas actually came from the U.S. The last piece in the film was about Iceland, and women specifically. Iceland had the first democratically elected woman president. Icelandic culture really supports women, and women are in the most leadership positions of all of the countries in the world. When I saw that I thought, I wonder how that is related to Bjork’s parenting, her approach, and her cultural framework for being a mom and an artist.

In that Instragram post, someone commented that Bjork had once said in an interview that in Iceland they just strap the baby to their back and keep going. That resonated with me because I did tons of work with babies on my back. That’s a great thing to remember. You can do a lot with a baby. I would cook meals, go shopping with the baby in a carrier. I couldn’t play, necessarily, but I could take them on tour with me. I couldn’t practice and write with them on my back, but there were so many ways that I could do both to keep the machinery of the household moving.

Of all of the women I’ve interviewed, so far, I don’t think anybody took a maternity leave longer than two months. In my case, just to be clear, I chose that. To choose that is a massive privilege. My situation is very privileged. For me, it comes in as it comes in, and there’s additional income that comes in if I do a tour, but the other stuff is just coming in as royalties, whether I tour or not. Although there is a fear that if I stop touring I’ll stop seeing those royalties. People will forget that you’re there, or they won’t know that you made a new record. You have to stay out there to some degree.

I’ve been really lucky, and I’m one of the only musicians I know who can live off their royalties. So many people are in bands; they’re not the primary songwriter. They’re on a major label, so they don’t own their own music. They don’t have a support team, they don’t have a manager, they couldn’t keep it going, they have to be out on the road to make money. There are a million stories. I am really lucky. I work really hard, and my husband works really hard, but there is privilege and luck involved.

What projects are you most proud of over your career? I’m proud that case/lang/veirs came to life, because that was really hard. Three really strong-willed women, serving as people coming together and working on songs together. It was really cool, and it was really hard. Just getting in the same room together and accomplish anything was really hard. The writing process took three years, and the production and release took another year.

What was the motivation and the inspiration to do that project in the first place? k.d. lang emailed us one day and asked if we wanted to start a band. She had met us both separately and I think something just clicked for her, and she wanted to work with us both.

She started it, and I did a lot of the writing because that’s one of my strengths. I wrote a lot of material for them, and we would get together and change it around. They would drop in their own lyrics or we would change structures, but there was something to start with. Lyrically, Neko Case is brilliant, and k.d. lang is a master of performance, singing and execution.

I’m also proud of various records that I’ve made. Certain ones just hit the mark. “July Flame” is one of my best. I’m really proud of the new album. I really poured my heart and soul into the writing. I worked four days a week every morning, writing two or three songs a day for a year. I really stuck to it, hard core, office job style.

Do you like working in that way? You hear about parenthood making you more efficient, more wise with your time. But I think there is a dark side to that too. I would go up there with a mindset of having to just produce. I would forget to chill, slow down a little bit, remember that this is music. This is not making a table. There is creativity in making a table, but when you make a table, you check things off a list. With a song, if you’re going to conjure something that’s meaningful, it requires a little bit of spacing out, relaxation, dreaming. Things that you don’t associate with motherhood at all.

That’s been a learning curve, and I’m still learning how to just chill for a minute and take space to be still and be quiet and not efficient. Art is not about efficiency. It’s about other stuff. It’s about connection to the gods, or something. I’m not religious, but obviously I do feel that sometimes, that what I’m striking is from beyond. That’s what people feel when they’re moved by music. They’re moved in their soul and spirit, and that’s what a musician gives: their soul and their spirit. If you’re just up there turned off, trying to be efficient, it’s not going to happen.

In my experience, sometimes the most important parts of the creative process are the in-between moments, where you allow the chaos and dust settle before putting all of the pieces back together again. And at the same time, if you’re just letting dust settle, you’re not going to produce. For me, once I’m in a flow, writing every day for weeks, then stuff can sort of do both. Dust is settling while I’m creating.

What is your favorite thing about being a mother? Watching my children. I saw this quote: “Children are magnets to their mothers’ eyes.” They are a magnet. I want to stare at them. They are so beautiful. They are so full of light. They are joyful. They are passionate. They are artists. They’re alive. They’re like bursts of light. They are sunbeams of the house, and it’s such a miracle that they are here.

“Take the risk. When you become a mother, you’re taking a big risk, risking your own heart every single day that your child is alive. When you’re an artist you’re also taking a risk. You are risking your vulnerability, your income, your stability. But when you can do those things and embrace them both, you will have a full life.”

What advice do you have for other Mother Makers? Go with your gut, because there are a million different ways to do this. You can take 16 years off. You don’t need to be wildly productive as an artist while you’re being a parent of young children. But if you want to create, make the space and time to do that. Find a way. You can do it before they’re up. You can do it after they’re down. You could hire a babysitter. You could do trades with friends. You could have your mother-in-law come in, or you could make sure your partner is active in letting you have your space.

I definitely encourage people not lose themselves in motherhood. Don’t forget you’re an artist, but also don’t become so obsessed with your career and ambition that you forget you’re a mother. I think very few people skew that way; I think it might happen a little more often with the dads.

Cut your own path. It’s risky. Take the risk. When you become a mother, you’re taking a big risk, risking your own heart every single day that your child is alive. When you’re an artist you’re also taking a risk. You are risking your vulnerability, your income, your stability. But when you can do those things and embrace them both, you will have a full life. It is a privilege to be an artist, and it’s a privilege to be a mother, too.