Being an artist mother is kind of becoming more acceptable now, and people are talking about it. I’m really grateful to be having kids in this day and age, for that reason. But I knew that even in the last ten years, things have changed a lot in terms of acceptability, right? It absolutely has. Everything from mommy blogs and all of that stuff. My kids are 16 and 14, and none of that existed for me as a parent, let alone an artist, so it’s fun to be part of this effort to celebrate that this is a really valid way to merge all of your lives together. I’ve started loving doing things that are centered around motherhood, because I feel like it’s the first time professionally that I haven’t felt like I had to apologize for that real life stuff.

What was it like when your kids were small, in regards to being an artist? I actually wasn’t practicing any kind of art when we had children. I had gone to school for art out East, and then I moved to the Midwest for a completely different type of job. Then I met a guy who wasn’t involved in the arts. I had moved to the area and I hadn’t really connected with people in the arts because I came for a different type of career. I had sort of put that whole part of me on a back shelf. Then when we had children, we made a decision that I’d be a stay-at-home parent. So I left even that career that I was doing at the time, happily, to focus on being an at-home parent.

“We got married and we had children, and I decided to stay home, and all the creativity came gushing out in the form of birthday parties and things like that, which I had a blast with.”

Had you gone to school for art prior to that? Yeah, I did. I was always the kid that was the artist in class, and I was going to summer programs at universities and studying it really seriously all through high school. I went to school in West Virginia at a small school, but a really beautiful area in the pocket by Baltimore and DC. There was a lot of great culture, and a wonderful art program, and I studied graphic design and printmaking. But by the time that I finished college, I wasn’t interested in graphic design anymore. When I went in, it was a lot of hand work, and maybe screen printing and things like that, and when I graduated it was all computers. I don’t thrive artistically on a computer. It’s sort of all I can do to maintain my website. I think that graphic design is amazing and I love it, but I didn’t want to execute it anymore because of the technology.

So I got a job with Quad Graphics, based here in Wisconsin. They had an administrative trainee program, where they really wanted students right out of school that would be super flexible in their business. You’d spend three months in every department under the sun, under the whole company, and were often bouncing from plant to plant, within Wisconsin. I was completely out of the artistic world, but it was a really flexible career. They sent me to New York state for training, and New York City, and it really appealed to me. I had finished school and didn’t want to do my major, but I wanted to move out and have health insurance and all of those things. I moved to Milwaukee from the East Coast, and I loved it. I love Milwaukee. And then I met a guy who was from here and establishing his career, and I stayed longer than I thought.

We got married and we had children, and I decided to stay home, and all the creativity came gushing out in the form of birthday parties and things like that, which I had a blast with. I really loved focusing on being an at-home parent. But those birthday parties only come once a year, so I just had a big missing part of me.

Those years when you were a stay-at-home parent, what was the process to discovering you needed it back in your life? I was a stay-at-home parent for four and a half years. I was just unfulfilled. When you’re a mom and you say you’re unfulfilled, that feels like a horrible thing to say. But I had a great network of mom friends who were one-by-one going back to work, or going to consulting or freelance work. They were kind of reestablishing the career part of themselves, and I wasn’t interested in going back to work outside of the house in any of the careers that I had flitted around in for the eight or so years prior.

“I started seeing a counselor for a couple of these issues, trying to figure out what was making me feel not happy. She zoned right in on it: “Wait a minute…you were always an artist. What do you make now?’”

I started seeing a counselor for a couple of these issues, trying to figure out what was making me feel not happy. She zoned right in on it: “Wait a minute. You said you went to school for art, and you were always an artist. What do you make now?” She saw it way clearer than I did. So we immediately carved out a tiny little corner in the basement for me to have a studio, and I just started making things again. I started playing around with materials. It was a really fun time to just explore materials.

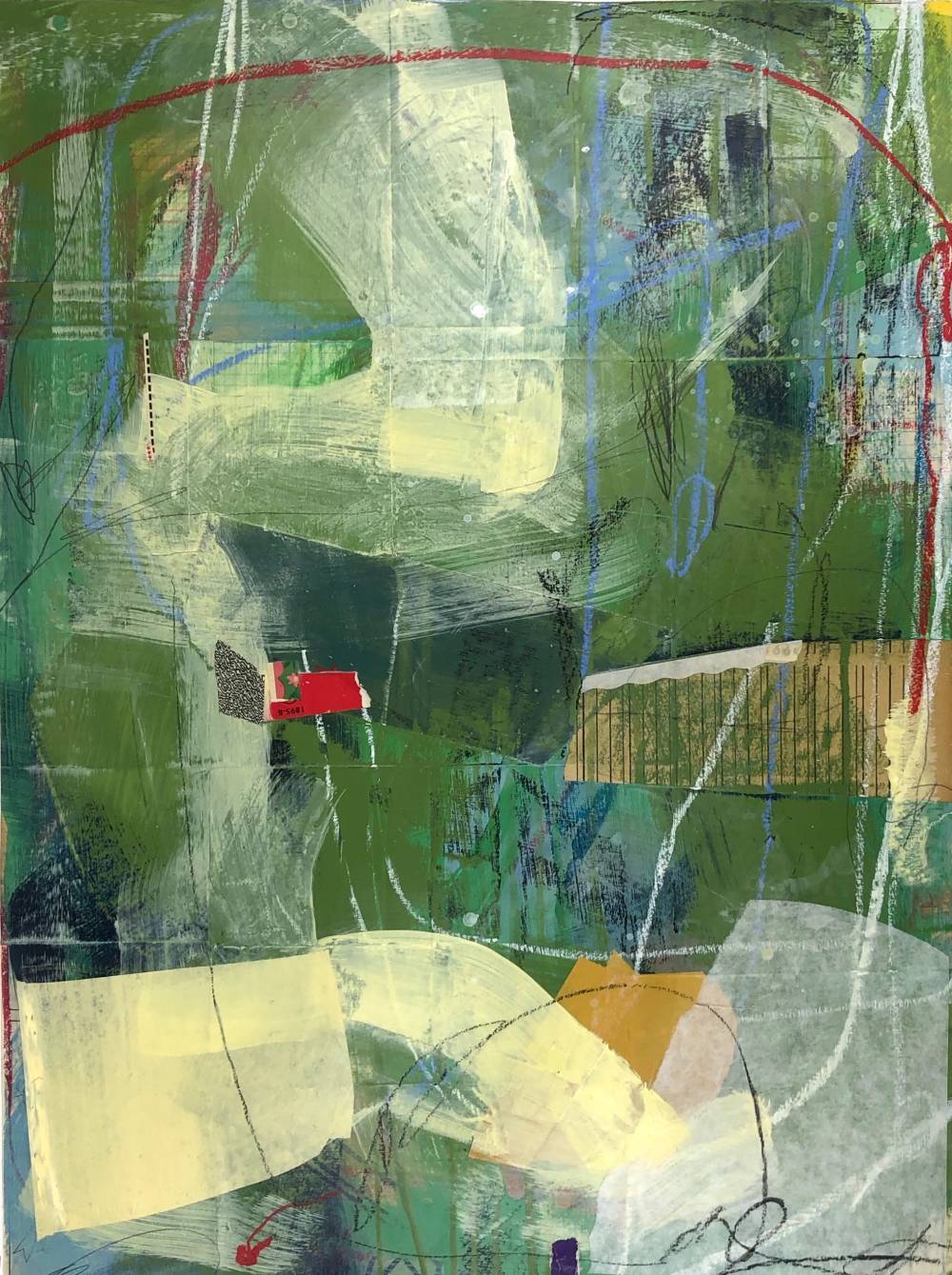

The medium that I really thrived in in college was printmaking, which requires a huge press and all of this equipment, and isn’t available in a little starter home basement. So I started playing with materials that would ultimately end up being the materials I use today. I am a mixed media artist. I layer a lot of collage elements and paint, and drawing tools, and anything I can reach. And I was always like that. I always liked to merge different materials together. My mom would tell you that my bedroom was always a mess with tiny little projects and every art supply you could possibly have. So it was very rewarding to get back into that, with no goal, really. That’s a real gift, to just be able to see it as exploring and playing, and it wasn’t because of a deadline or an obligation or outside expectations.

Did you see a noticeable change in your mental health and your well-being from the very beginning, or was it a process? Well it was probably a process, but absolutely I am sure. I always feel better if I’ve painted something or made something, and really what was the big deal was carving out a physical space in our home that was dedicated to me doing something just for me. It was sort of sandwiched between the laundry room and the storage area of the basement, but I made sure that when I went there, I closed my eyes when I went through the laundry room so I wasn’t thinking about laundry to do or anything like that. My husband was just fundamentally supportive, and everything happened really quickly because he was like, “Oh, we’ve gotta do this now. Yes.” Being allowed to claim a portion of myself that wasn’t about being a mom was really important.

How long did you do it as a hobby before it became something you could build an income from? I first started making things just for myself, and then I would make gifts for people. A lot of the work that I was doing was drawing from the notion of parenting, so making a gift for a friend who had just had a baby. It made sense that what I was making would fit that sort of occasion. And then it got to the point where I had a bunch of stuff piling up. And I did go to school for art. You want to make things and then have it be seen. So I started reaching out to little boutiques or stores. Sometimes they were children’s boutiques, just the places I was spending my time. My work fit really well in those sorts of spaces. But what was funny is the sales didn’t come fast from their customers. Honestly, it felt like their boutique was just really nicely decorated. It wasn’t clear that this was for sale. But it was encouragement from outside of my family, and outside of my home.

I think it was 2007 was when we created that basement studio. And probably within a year or so I had enough work and a friend that connected me to a space in the Third Ward where I hung work for a gallery night weekend. Then that shop kept my work hanging for a month, so that felt like my first show. I had to create a body of work of like 20 pieces. I brought them in at one point and the shop owner said, “I love these. Could you go bigger?” So there was this encouragement to try and stretch, with a deadline and framing, and have it ready. Then I also had to think about pricing and all of that stuff.

We were living in West Allis, this little community off the edges of Milwaukee, and then when we moved to West Bend around that same time, which was maybe 2010, I had a show ready for a restaurant that did really nice art shows throughout the year. I had approached them, and they were booking their shows a year out in advance. So that was a really new experience for me, in terms of the realities of the professional experience of showing your work. It’s not like you say, “Oh, I’ve got 15 paintings. Would you like me to hang them on your wall?” Often places that have a deliberate approach, whether they are retail establishments or restaurants, they are booking their wall space out a year in advance. They liked my work, and they put me in for a year out, and that meant that I had to keep being an artist for a year. That was really exciting and encouraging. A little daunting too, because early on as an emerging artist there was this feeling of, “Am I going to be able to keep making good art for a year? Do I still have a voice?” And all those experiences just kept me working, and really kept my work growing.

Did you ever have any feelings of doubt over what you were doing? Yeah. Absolutely. I think there’s that imposter syndrome that everybody talks about from all sorts of different fields, but it gets a lot of attention in the art world. And I still have that. I still have that feeling. I was messaging you, saying I was nervous about doing this interview. Because even though I studied art all along, and I had really great educators and really great support, I was just sort of always surprising myself like, “Look, I can still do it!” I have always felt doubt, but I’ve never felt like I shouldn’t be making art.

There have been times when I’ve taken little pauses in the last 12 years, for just the reasons that sort of interrupt your flow, and been worried that I was going to get back to the studio and nothing was going to come. And I remember having a conversation with a woman who was older than me who had an awesome perspective. She said, “You know, you’re an artist. You’re never going to not be able to make art. And if you take a long break and you get back to the studio, I don’t believe you’ll ever find that you can’t make art again.”

“Those pauses are like when a field needs to go fallow. It requires that break, and things percolate under the surface so that you can’t really predict how they’re going to come out.”

Those pauses are like when a field needs to go fallow. It requires that break, and things percolate under the surface so that you can’t really predict how they’re going to come out. I’ve had a couple things like that where I’ve had a phase of making a lot of art and then a phase of taking a little bit of a break. The returning is always a little nerve wracking, and then something comes out that lets me know that I can still say what I want to say with my art. There are always pieces that turn out terribly ugly, or aren’t what I want to say, and those go in one pile, but in general I’ve grown to be able to trust those fallow periods and just get over the hump again and get working again. It keeps being proven that even after a pause, the work that comes next is exciting, and an evolution .

And to think about it, your whole career started after a long pause, right? It absolutely did. And what’s neat now at this point, is that I can look back and see connections of what I’m doing now that are connected to what I was exploring in college. Some of the fundamental things that I’m interested in about being a human are still the same, and those are the things that I’m always toying around with in the studio. So that’s kind of exciting to see, too. There are always these evolutions, but it makes sense. It’s still my hand, and it’s still my voice.

What are you currently working on? What are you interested in exploring right now? I really love thinking about how we are made of a million different moments and experiences that sort of all pile up and make us who we are in this hour and in this phase in our life. I had the chance to do a little artist residency at a middle school once, and I honestly think I explained it to those kids the best: “Who you are right now, as I’m sitting here talking to you, is informed by whether your alarm went off at the right time this morning, whether there was the kind of cereal you wanted for breakfast, whether your brother or sister was nice to you, or obnoxious to you, whether you got to school on time and had your homework done, and you got to sit here next to your friend or not. All of those things made you who you are right now. And the person sitting next to you had all those same sorts of experiences that make them who they are right now, and just the fact that you’re sitting next to each other, and we’re all having this conversation is still making you who you are.”

I love feeling like we’re all having private, individual experiences, but there’s a real interconnection to what everybody is going through as a person. And I find that the way that I like to try to explore that with my art is by layering up literal different materials and brush marks and drawing marks in a variety of ways. So there are areas in my paintings that have some real precise mapped out clean qualities and they might get covered over by really expressive brush marks or scribbly kinds of lines. And then more, I use a lot of collage elements to physically create these layers. There might be more really precisely cut out collage areas and more scribbles. I just really like layering those things up and combining precision with chaos to explore this balance. Right now in the last six months I’ve gone to paintings that are completely non-representational abstract, so they’re really just marks of color and line and they don’t reference any specific recognizable shape or concept, because I’m just going all the way into exploring the idea of all these layers of us that make us who we are.

When your kids see your art, what do they say? They’re so candid and great. When we moved to our second home, I actually got a studio upstairs with a window, and it was bright. It was the spare bedroom. I was doing a long series. I’ve always used a house shape as a metaphor that I’ve explored off-and-on throughout the years. At this point I was doing a lot of houses, and I was also doing a lot of pieces with birds on them, and my youngest son came in at one point and just laid down on my studio floor and looked up and he went, “What’s with all the birds and houses…?” It’s like, “Well, someday you’ll learn I like to work in series for a really long time. They’re what I like to do.”

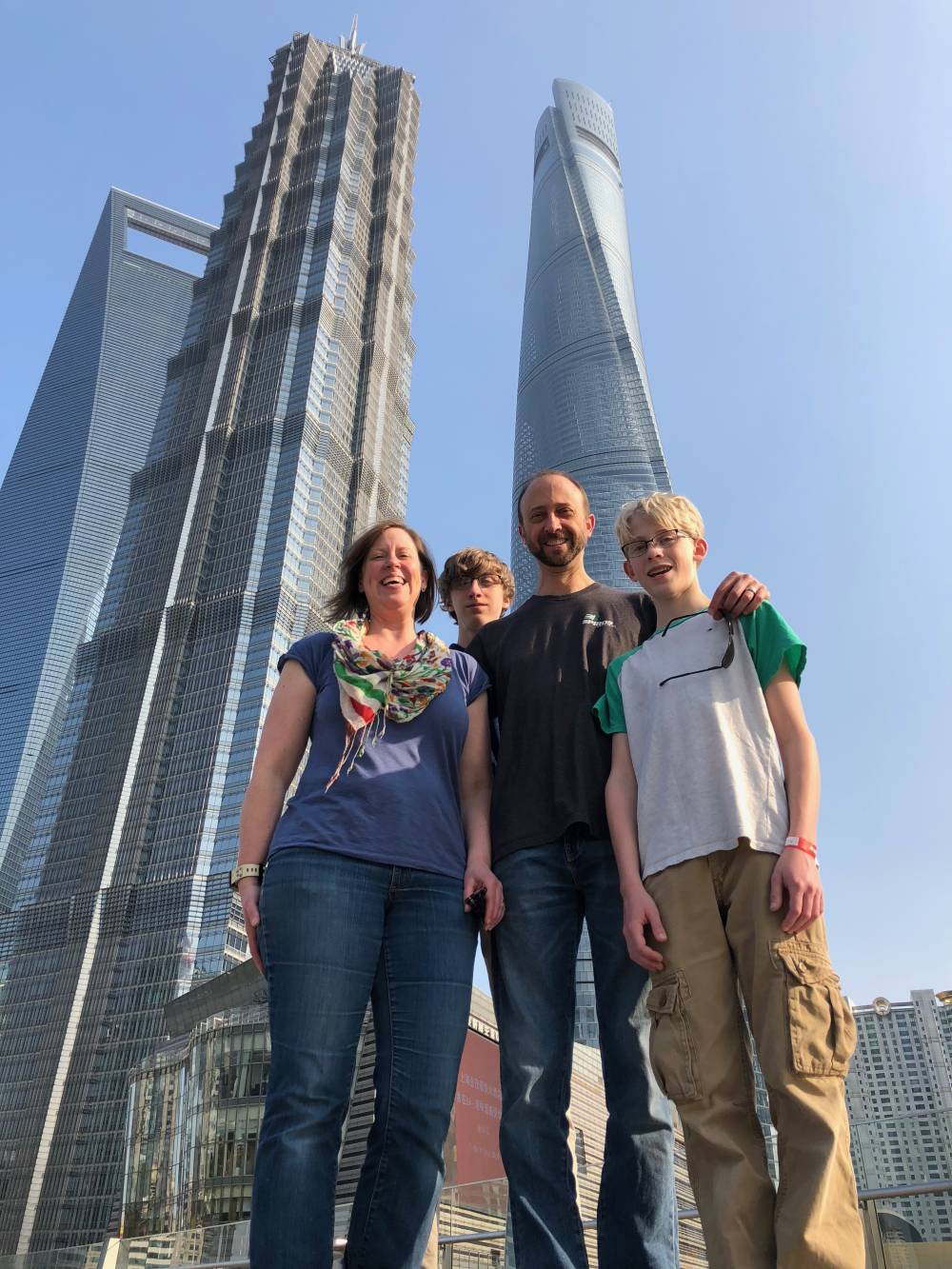

My kids are incredibly creative. They are 14 and 16 year old boys. They have their own maps that they are charting personally, so they’re not painting with me, they’re not into art museums. They’re not really into art shows. But they come to my bigger events and my bigger openings and I think they’re proud of me. Or they think it’s cool, or they see this sort of success, but also they think it’s kind of no big deal, like this is just my job. And I’ve gotta tell you, I love that so much, because even though I studied art, growing up there was a real hesitance on my parents’ perspective to be able to support going to college for a fine art degree. It was just too scary and nebulous, and in the early nineties there was no internet to connect us, there was no Instagram to promote your work. So there was a much bigger feel of, “What? You’re going to be a painter? That could mean that you’re starving, and living in a shitty studio in New York!” So the graphic design degree was kind of a compromise. I could be an artist but also get have a career.

For my kids growing up, seeing that being an artist is just a totally normal and appropriate way to make your space in the world and make a living is a real gift to to them, I hope. It’s the idea that if you’re really passionate about something, you can figure out how to make it happen. And again, I think they’re really lucky to be growing up in the digital age because there is no end to the ways you can create your own career, no matter what you’re interested in.

In raising kids for 16 years now, what kind of things would you tell yourself, looking back, about how to proceed and get to where you are now? Would you change anything? I do have this perspective that your experiences layer up to make you into who you are, so I wouldn’t change anything drastically. I would love to have gotten to a place of confidently calling myself an artist earlier, and speaking about my work more confidently earlier. Knowing that it is a valid way for me to spend my time. It’s hard sometimes to have confidence in your work, and your ability to call yourself an artist.

I’m in my mid-thirties, and I do want to talk to people who have kids who are much older who have been through it, because for me, and why I do this project, is because it’s hard. It’s hard to convince yourself that you can continue doing what you love and raising kids at the same time, and that you have value beyond being a parent. It seems like you’re really settled in who you are now. I just suspect that hasn’t always been the case. I chose to be a stay-at-home mom, and that was a choice between both my husband and I. At the time that we had our first son, I had left Quad Graphics and I was actually doing development, fundraising in the arts. I was never making a ton of money. So financially it made the most sense for my husband to stay on his career track, and I think there was this real chemical, visceral need for me to be home with my babies. Then, five years later, wanting to carve out some time for me to do this hobby felt appropriate for me to be like, “I need a little space to myself.” But it was still in hobby mode.

Then even at a certain point we hired a babysitter once a week so that I could get three or four hours to run some errands or do some art, and that’s sort of how I got enough work together for one of my first shows. And that felt pretty great. As long as I felt like I could sell enough pieces to cover my art supplies, I felt like this was a hobby that was supporting itself. I was still a full-time at-home mom, and I was doing this thing that wasn’t impacting our budget and I could squeeze it in, but my priority was still being a mom. Definitely once the kids were in school full time and my art was taking more of my focus, my identity was becoming more attached to it. I had a really hard time feeling like dedicating lots of time to my art was appropriate. If I did that, then who was going to take up the slack in the hours of the day that I had been doing household stuff?

“I felt, honestly, this sort of voice from really deep within say, ‘Yes. You need to do this.’”

I hate that it makes it sound like we had this sort of 1950s dynamic, but the truth is my husband was earning all of the money and all of the financial contribution to the family, and in the eight hours a day that he wasn’t home, I was running the house. I had a lot of guilt about carving that time away. There was a little shift when the kids went to school, because it was like, “Oh, well I can do this now because they’re not here.” But as soon as anybody else was home, I had a really hard time concentrating and giving it that space.

I took a part-time job at the art museum up here in West Bend when my kids were in elementary school, because I was lonely. I’m an extrovert, and once they went to school and I was working in this little studio once in a while in my house, I wasn’t getting out and interacting with people. So I found a part-time job at this museum, and I loved it. I let myself take one of those hiatuses in my art for about 18 months. I knew that I would come back to it eventually, but eventually the job really required a full-time person, and I didn’t want that, so I stepped away from it. I didn’t really have an intention, like “I’m stepping away from this so that I can do my art.” It just was no longer a good fit, that job. But the week that I gave notice, a friend of mine in West Bend who had just rented a studio space and was a fiber artist, just saw me out of the blue and said, “I’m running a studio and I have an empty room that’s not being used. I want you to sublet it from me, and I want you to have a studio and start making art again.” I felt, honestly, this sort of voice from really deep within say, “Yes. You need to do this.” And I really mean that when I quit the job at the museum, I didn’t have a “I need to quit this job so that I can make more art.” I knew that I would always make art, but that wasn’t the reason. But as soon as this friend offered this up to me, I just knew that that was the thing that I needed to do.

I went home and this conversation with my husband went: “Okay. So you know how we decided we could afford for me not to be earning an income at my museum job anymore? So now, I really want to rent this space from my friend…” I mean it was so cheap. It was like 85 bucks a month or something. “So now, not only am I not going to be earning any money, but I want to be able to use family money to rent this space.” And he said “Okay, absolutely. You need to be making art again. Do you think you’ll be selling enough regularly to cover the rent?” And I said, “Well, I need at least a year for that not to be an issue. Because I haven’t made art in a year and a half, and I don’t know what’s going to come out.” And he’s so great. He was like, “Okay. We can figure this out.” And we did, and it was the greatest boost to my career.

There was something about shifting to paying money to rent a space outside of my home. I think the biggest thing was that it was outside of my home. I had to put normal people clothes on and leave the house and go there. So if I was working on a painting and it didn’t feel like it was really going anywhere, the choice to ditch it and leave was so much harder. If it was my studio in our guest room, I’d just sort of walk down the hall, but in the studio I developed a much stronger practice. Then I started having really great pieces evolve because I was putting all that effort into it.

But still, to be clear, we are a single income family. We’ve really always structured our income and our budget to the best of our ability to be based on one income, and we are incredibly lucky that we can do that. I’ve been privileged to be able to not have a financial burden on my art for the first many years of it evolving. I think the little alchemy of hard work and timing and a great art education means that I’ve been making work that has been selling. So for most of the time that I’ve been making art I’ve been able to cover my expenses, and then it started creeping up a little bit. It kept feeding into the art, because we still didn’t require it for our family. Having that freedom really allowed me to dive in to the craft and explore different ways of selling and making art.

I’ve tried art fairs and juried shows and grown sort of slowly in that regard. About two or three years ago, I knew that I wanted to push even further in terms of selling my work, and I knew that meant that I was going to have to devote more time to make even better work, make more work. All of that is more money and more time and hauling your work around to show it. I do summer art fairs, where I set up the tent and I show my work in Chicago and things like that.

You know how earlier I had said I was a stay-at-home parent? All of a sudden realized I couldn’t keep up with my end of the way we had divided homeowner responsibilities and parenting responsibilities, and we needed to make some shifts. It was hard, because it took awhile for me to realize what wasn’t balanced right in our family. My husband and I sat down, and I literally had a conversation like I was requesting a change of job responsibilities: “For 12 years or ten years or whatever, I have happily been filling these responsibilities, but my interests have changed, and I’ve grown, and I want to do this now. It’s going to require that some of these things have to shift.” Which, obviously, we’re a department of two. They had to shift to him. And he was awesome.

That was a really difficult part, but only because we had to redefine things. Now, like I said, I have a 16 year old son. It’s still really hard. I have been doing this for 12 years. It’s hard in a new way right now. Because my kids are getting ready to go to college. And college is really expensive. And I feel like as a parent, and again, this is also coming from a voice of privilege, but my kids are able to manage college and I believe that it’s an important next step for them. I believe it is largely our responsibility as parents to make that possible. I mean, college now costs way more than it did when I went to school, so I do know that we’re not going to be able to afford every penny of it. We’d always sort of had this vision that when our kids were in junior high and high school, I would go back to work, and my income would largely fund college. And that’s a really tall order for a visual artist to fill.

Now that you’ve been doing this for so long, how could you possibly stop doing it? It’s really interesting, because probably about two years ago, I thought, Ok. I’m really setting an intentional goal. I had a goal of making $30,000 a year from my art, because I thought also, realistically I had a small runway in terms of career, corporate-wise. I have been out of the work force largely for 16 years. I know I’m smart and I bring a lot to the table, but it’s hard to quantify it on a resume. I know that if I went to a corporate job, my starting salary would be not huge. So I thought to myself, why can’t I make basically an entry position salary, doing the art that I know I’m an expert at? I don’t mean that I’m an expert in the field of visual arts, but in my life, this is the thing that I’m the best at, and the skill that I’ve really honed.

I had this well of confidence. It was a similar boost of confidence that three years ago had encouraged me to take a studio outside the house. I just thought, No, you can figure this out. And I’m not there yet, I’ll be honest. I have really boosted my sales, but it’s because I’ve been going to art fairs further away, and I’ve been really honing my craft and increasing the prices of my work, and I’m working really hard to try and get my work in front of the right audience. That’s a big thing for all of us in creative fields, to determine who do you want to be speaking to, and then figure out how to find them. I think that my work resonates. I have a lot of really great feedback on social media and I’m just reaching into new gallery spaces and new juried events, so it’s going. But the money part is still scary.

In the last year or so, I’ve been doing some work with an online business coach that focuses on women in the creative business, entrepreneurial sphere, and some of the earliest work that we did was in redefining success. What’s really interesting is that I joined this year-long coaching program thinking, Ok, my goal with this year is to really hit that $30,000 a year mark, and within the first month I had redefined success to say, Well actually, if I’m still making art that is growing and reaching new audiences, and I can aim for gallery representation and maybe a little bit of less sales, and if I need to take a different type of job that will support the college goals, that still feels like a success. It’s an interesting switch. I think two years ago if I had had to make that choice it would have felt like I got forced into it by failure, and now I actually feel like if I ever do get to that choice, it’ll be because it was the right choice to make. But I have no doubts about my work resonating and being strong and growing and appealing.

“…you’re just showing your kids that as a human you have these inherently valuable gifts to share, and the work that goes into making them come true is valid, hard work.”

What advice do you have for other Mother Makers? If you have something in you that calls you to create, don’t ever undervalue that. You can’t quantify it with whether you support your family or you change the world. If you have something that you’re uniquely able to create, the world deserves that, and needs it. It is a hard life. There’s this mystique of “Oh, being an artist or being a musician: that’s such a hard life, how could you ever do that?” And I think if you can let go of that “It’s such a hard life” worry, then what comes out of it is this blooming of this amazing thing that only you can create, and only you can share. So if you have the opportunity to do that, don’t ever feel like it’s not a valid way to spend your time.

As far as being a mother and an artist, you’re just showing your kids that as a human you have these inherently valuable gifts to share, and the work that goes into making them come true is valid, hard work. And honestly, if we can show a whole generation of kids that being an artist is a totally typical, normal, awesome, important job, then that’s only going to make everybody’s path a little better.