Tell us about you and your family. Most people call me Addye, which is a family name, after my great-grandmother. She was a maker, an artist and an entrepreneur. It’s also the name of one of my older cousins who I have always looked up to, also an artist and a maker. When my husband and I started dating, I was still going by my full name, and he came up with calling me Addye, out of the blue. It fit, and it was an interesting coincidence.

I am 35 years old and I have three boys, ages ten and a half, seven and a half, and four. I live with my kids and my husband in New Jersey. We just recently moved back here after living in California for six or seven years.

Why did you decide to move back to the East Coast from California? We decided to move back for a lot of different reasons. One was the recent presidential election. When we woke up the next day, one of the biggest concerns that we had was health care. At the time, my husband was working for a startup, and we decided it would be best for him to go back to a corporate job. We didn’t know what was going to happen with health care, and that was important to us with three young kids. Two of our kids are autistic, and one has ADHD, so we need extra support.

Because my husband works in tech (software), he wanted to be able to travel for work. For me, it was important to have family around for the boys and myself. If he was going to be traveling and I would be solo parenting six or eight weeks at a time, I would need some more support. As much as I loved living in California, we were pretty much out there by ourselves. If I wanted to pursue my art career, whether it be doing residencies or gallery openings, or seeking out opportunities to exhibit my work in different places, childcare would be a huge issue. My husband is originally from New Jersey, and my mom and my stepdad are from Philadelphia. My brother and sister live out here. My husband’s core group of friends is out here. It just made sense.

Where did you grow up? I grew up as a military brat. My parents separated when I was around two years old, and I grew up mostly with my father, who was in the Air Force. He was stationed in Alaska, New Mexico, and Texas, where I was born. Then when I was 17, I moved to New Jersey.

How was art a part of your childhood? I was always a creative person, but I was never into visual art. Writing was the area in school where I was the most articulate, and excelled. I was reading at a junior high and high school level while I was in elementary school, and then when I got into junior high I started getting more and more into performance art. I joined the drama team and the debate team.

In seventh grade, I took an art class as an elective. And I remember my teacher looking at one of my still lifes and one of my paintings, and saying “You know what? You’re a great writer. You don’t necessarily have to be a visual artist.” And that solidified the idea in my mind that I wasn’t a visual artist, and that I couldn’t draw. In my mind at that time, I thought that if you couldn’t draw that meant you couldn’t be an artist.

Isn’t it interesting how impressionable we are at that age? One comment from a teacher can change your entire perspective of yourself. Yeah, that was a big moment for me. I just shut myself off from that aspect of my creative voice. I had always just thought of myself as a writer, and then later on I got into drama and dance and I was very performance based. I never picked up a paintbrush after that seventh grade class. That was it. I was done.

“I came back to art after a therapy session that I had in the year following my diagnosis with bipolar disorder.”

When did you come back to it? Interestingly enough, I came back to art after a therapy session that I had in the year following my diagnosis with bipolar disorder. I had been experiencing hypomanic symptoms and I was explaining the intensity of that agitated state to my therapist. I didn’t know what to do with the intensity of it. I felt like I couldn’t escape it and I didn’t know how to cope with it. Her suggestion was to try to channel it into making something with my hands. She knew I was creative as a writer, but she insisted that there is something different about making something with your hands. She suggested I try knitting or crocheting.

I had tried to crochet with one of those looms back when I was a kid, so I thought, maybe I’ll try that. A couple days later I went to Wal-Mart looking for a crochet hook and some yarn. As I was walking down one of the aisles, I passed by a section of cheap craft paint and brushes and little canvas boards. On a whim, I threw some of that stuff into my cart.

I tried to crochet for about two weeks and then abandoned it because it wasn’t working for me. My kids were with my partner at the time (now my husband) for the weekend, and I was feeling kind of alone and agitated. I wanted to do something for self care, so I thought about what my therapist said and looked at the paint that was sitting in my room and thought I would just try it.

I didn’t try to draw anything representational. I just spent about 45 minutes pushing paint around this little canvas board with a brush. I realized when I stopped that a lot of the agitation and the ruminating thoughts that I had been having - the brain chatter - had died down. I felt calm, which was something that I was not used to feeling during that period of my life. That’s how it started. There was no intention of having it become part of my identity. It was strictly therapeutic, to manage my mental health.

How old were you at that time? I was 29 and a single mom of two. My partner (now my husband) and I were on a break. I was a full-time college student and I was trying to manage school and the kids, and also this new diagnosis. It kind of just became an outlet that I didn’t anticipate. I didn’t realize I could express myself in that way.

What are some of the things that led up to your diagnosis with bipolar disorder? My father was very abusive, so I grew up with a lot of generalized anxiety and trauma. As a teenager, I had frequent experiences with depression and anxiety. Even when I was in the military, there were some events that triggered depressive episodes for me, but I never really had a diagnosis beyond “You have depression” or “You have some anxiety.” It wasn’t until I got pregnant with my second child that I started having some really discomforting symptoms.

When I look back at that time now, I can see that it really was anxiety, and it was manifesting in a lot of physical symptoms. For example, I would go to the emergency room because my heart would be racing, and I could hear it pumping in my ears, and I would think, “What’s wrong with me?” They would hook me up to the monitors, see my pulse was through the roof but that everything else was fine.

After he was born, that anxiety just intensified. When I talked with my OB about what I was experiencing, he wrote me a prescription for Zoloft, and said I should talk to someone. That within a few weeks I should be fine and I probably wouldn’t even need to refill the prescription. As it turns out, Zoloft was a bad choice because it triggered a rapid cycling onset of bipolar disorder in me. In people who are biologically or genetically predisposed to bipolar disorder, taking an antidepressant by itself can actually trigger the symptoms. They normally don’t prescribe just that, but my OB was just trying to help a woman who may or may not have had postpartum depression.

“I didn’t have any language for what I was experiencing. I didn’t understand that because of my childhood history I was susceptible to postpartum depression.”

I spent the first year of my son’s life really struggling with fluctuating mood. I would be dripping with sweat. I had a lot of intrusive thoughts. It was a brutal experience. When he was almost a year old I started having suicidal ideations. I was so desperate for an answer, and I tried seeking out help. I had been told by one therapist, a social worker, “well, you know, women like you…” (meaning, black woman, single mother, two kids, basically on welfare, in a relationship that has its own ups and downs)…”well, it’s just stress. Anyone in your situation would be experiencing this. I don’t think you have postpartum depression or anxiety. I think you’re just stressed.” My primary care doctor told me I just needed more sleep. It had been a year of me trying to figure out what was going on with me, and repeatedly being brushed off.

I didn’t have any language for what I was experiencing. I didn’t understand that because of my childhood history I was susceptible to postpartum depression. At the same time, my only concept of postpartum depression was from seeing the pamphlets in my OB’s office with the woman looking very sad and crying. There was nothing to explain the rage that I was feeling, the heart racing, the OCD.

One night I was having a really bad night and I just started googling. I came across postpartumprogress.com, a website that has guides that detail the symptoms of postpartum depression, anxiety and OCD in plain English. I learned that you can have a mix. You could have one, or you could have all three. That was the start of getting myself professional mental health help. Through that process, my postpartum-related symptoms started getting better, but the cycling moods just kept intensifying and getting worse. I wound up again being suicidal.

I was living in Philadelphia at the time, and I remember that as a veteran I could go to the VA hospital that was there. I remember wrapping my son to my chest, getting on the bus, and going to the VA hospital and walking into the mental health clinic. I walked in and said, “Hi. I know that if I don’t get some kind of help, I am not going to make it another two weeks.”

“[The doctor] started laying everything out for me in a very methodical, scientific way that just made sense. And as he was explaining to me what bipolar disorder is…I just started feeling a lot of relief. It just made sense.”

The intake psych took me in, sat me down, took my history. I explained to him what I was experiencing, and he looked at me and asked me if anyone had ever told me that I could have bipolar disorder. I said no. And he said, “It’s strange to me that no one has brought this up to you, considering your family and personal history. You’ve told me that you have a grandfather who was schizophrenic, so genetically you are predisposed, and you’ve also experienced trauma in your childhood. You had periods of intense anxiety and depression growing up.”

He started laying everything out for me in a very methodical, scientific way that just made sense. And as he was explaining to me what bipolar disorder is, and how it can develop and who is at risk, I just started feeling a lot of relief. It just made sense. I felt like I finally had an explanation. He even explained that the prescription for Zoloft triggered a rapid cycling onset of the illness.

Then he said, “The good news is, this is totally treatable. I’m going to give you a mood stabilizer today and I can guarantee you within 45 minutes to an hour you’re going to feel a lot better than you have been. Take it for two weeks, and by the end of those two weeks you’ll be seeing your new psychiatrist here at the VA. She’ll be able to talk with you about long term medical and therapeutic intervention.” That was the start of living with a diagnosis that made sense for me, and actually getting effective treatment.

When did you start painting? I started painting in 2012, when my second son was almost two. I was in college at the time studying to be a social worker. I had just gotten my associate’s degree and transferred to a career school. I was taking an art appreciation class, and one of my classmates told the teacher that she should see my paintings. I was kind of surprised because I had no intention of showing them to anyone else. But the teacher asked to see them so I showed her some pictures of my work. She looked at me and said, “First of all, I don’t understand how you’re a full-time college student with kids, and you have time to paint.” My response was, “I don’t know if you can really call this ‘painting.’” She told me that if I kept going and started focusing on ways to bring some intentionality to my work, in the same way that I do with my writing, that I would have some really good raw potential. That stuck with me, and pushed me to start exploring painting as more than just a hobby or for cathartic reasons. That was big for me.

Did you seek out any professional training? I did not. I just kind of kept going. It’s funny because if people ask me now what I did to get started, I tell them that for the first year I just played. That’s literally all I did. If I went to look up anything on YouTube or Instagram it was just to see what materials people were using, but I didn’t do any tutorials. I didn’t watch any videos or read any books. And honestly, I am very art illiterate. I am not trained in techniques, and I haven’t studied art history, so I’m still playing catch up in a lot of ways.

I learned that if I just played, that was where I felt the most free. Once, through doing some reading I came across the term “intuitive art.” Once I realized that people are making intuitive art, I realized that it was okay to just create without necessarily pursuing formal training.

It would be different if I wanted to do more representational work, and now that I am getting into more figurative work I am considering maybe taking a drawing class, doing more formalized skill-based training. But because I have been so focused on abstract art until now, and because my work has always been rooted in pure raw expression, I haven’t sought out professional training.

When you first became a mother, you weren’t painting yet. Were you already working as an artist when your third son was born? I wouldn’t say that I was working as an artist quite yet. I was still mostly focused on it as a hobby, although when I got pregnant with him in 2013, I did have some interest from people to buy my work.

I had opened an Etsy shop, and would post my work there and on Instagram, but it was still very much a hobby. It wasn’t until after he was born and we had moved to California that I started thinking about being a working artist who exhibits work. My work has something to say, and I want it to be accessible for people.

What is the process of transitioning from hobbyist to marketing yourself and turning your art into a business? Making that leap, I first started out thinking that I needed to do just that: make a business. So I took a business course run by a creative entrepreneur, thinking that I could sell my work and make money from it. I went through the course and when we got to the end, the teacher told me, “I don’t think this would serve your work’s highest purpose. I don’t think this is the kind of artist you are - into it for branding, marketing and selling.” Even though I tried, my passion wasn’t in it. So after all of that I made another slight pivot and went back to the reason I create in the first place: to express myself.

“I strive to live art, and I want my practice to be reflective of that. I want every extension of myself to be an example of my work, from the color of my hair to the clothes that I am wearing.”

I strive to live art, and I want my practice to be reflective of that. I want every extension of myself to be an example of my work, from the color of my hair to the clothes that I am wearing. I want to be saying something with what I make. I’m not interested in painting something just because it will look great with somebody’s couch.

Once I made that pivot, I committed to talking about my process more with my online community. From my experience, you don’t find a lot of artists talking about their work while it’s in process. Maybe once it’s finished, but not in process, and that was important to me. I wanted to share that with people because I’ve found that it helps influence my work. I realize that there is a very communal aspect to what I create. Getting feedback from people and hearing how they’re experiencing it informs my process.

Once I started talking more about my process, I began looking for places to submit my work, whether that was galleries that were doing calls for art, or museums that have emerging artist programs, or colleges and universities that were having open calls for shows, online publications, anybody that had an art department for their publication where they take submissions for images.

How has that worked out for you? Over the last two years I’ve had over 120 submissions, and out of those 120 I’ve gotten two yesses. It’s a very humbling experience, but also a good learning experience.

In any arts field, rejection is just part of the process and it’s an important part of the process for all of us. I’ve gotten to a point where I just apply for things without really thinking about it, because I know that rejection is part of the process. The best way to deal with rejection is to just get used to it. I submit just to try things out, then I learn from the experience. If I don’t get accepted, I learn how much I wanted it and it forces me to examine why. There is a lot that I’ve learned from the process. It’s brutal. It’s intense. I’ve had moments where I wonder why I force myself to do this, but I think it has been good for me, especially being self taught, coming from completely outside the art world. I know nothing about having a traditional art career. I am basically a rookie.

Are you a full-time artist now? I am a full-time artist. I am a stay at home mom, and that is what I do in my spare time. I steal time. I make in-between moments and little cracks and crevices, all the little pockets of time that I can find. With my youngest, sometimes I was painting with him on my back, or he was in his rocker right next to me. Now, he’s pretty much my shadow in the studio. I’ll be working on a piece and I’ll look down and he’ll be painting a corner of it, unbeknownst to me. I’ll think he’s on his iPad or watching a video and he’s like, no, I’m right here with you.

Do your kids inspire your art? My kids do inspire my commitment to use my work to speak to specific things, maybe things that are race related or wanting to offer my perspective on living as a black woman who has black and brown kids.

“I want my kids to see their mom not just surviving motherhood or surviving her life, but living it and thriving and pursuing it.”

I am deeply committed to wanting to stay a whole person. One of my biggest frustrations after having my oldest son was that the messaging that I kept getting, that as a single mom I needed to give up my own dreams and ambitions. Basically becoming a mother meant that I had to derail all of that and I needed to become, for example, an x-ray technician. I needed to do whatever it would take to survive. I didn’t pursue any dreams or ambitions that kept me connected to who I am. Since then, I’ve always fought very hard for that and I want my kids to see that. I want them to see and to understand that their mom isn’t just their mom. As much as I love them and I love who they are, they are a part of my world but they are not my whole world. I am more than just their mom. I am a person, with my own dreams and desires and insecurities.

I want my kids to see their mom not just surviving motherhood or surviving her life, but living it and thriving and pursuing it. As a feminist raising boys, it is important that they see that. Mom can be a lot of different things, all at once even.

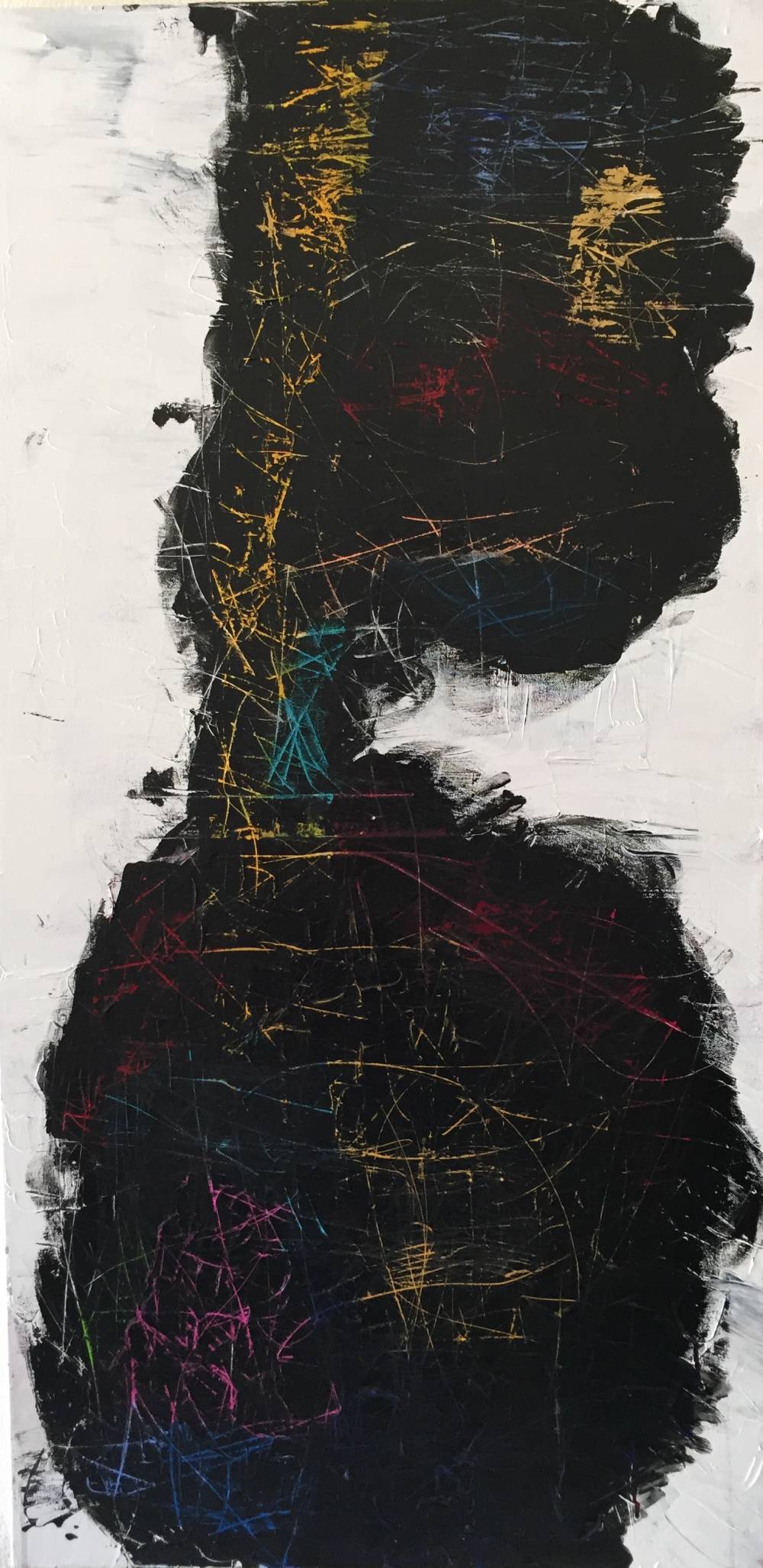

In regards to your Art as Protest series, how has making these pieces helped you process injustice? In the most simple way, it gives me a way to process it. Writing has always been my default. When Trayvon Martin was killed, I wrote about it first. It took me another year and a half before I actually tried to process it using painting. But what has happened over the last few years is that writing has fallen back, and painting has become the default for me to channel that raw emotion.

Painting gives me the space to just allow the emotion to come out. Because my work is based on intuition and is abstract in nature, it allows me the opportunity to express myself without the burden of wondering how people will interpret it. I have learned that if I write about what I am feeling about injustice, people will pick apart my words.

“An image can pierce, subconsciously, in a way that words cannot. An image can grab you before you’re even aware that it has, and can seep into your subconscious and bring things up for you that you might not even realize you are experiencing.”

An image can pierce, subconsciously, in a way that words cannot. An image can grab you before you’re even aware that it has, and can seep into your subconscious and bring things up for you that you might not even realize you are experiencing. With words, people can jump too quickly to defensiveness, but an image opens you up without even realizing it. Using art allows me to not worry about my tone, my presentation, if I’m being too much, if I’m being the “angry black woman,” if I’m being too aggressive. Using art allows me to just be.

What are you most proud of as a mother? I am most proud of the fact that my kids have this space to be who they are. I grew up in a very abusive household where I wasn’t allowed to be expressive. I wasn’t allowed to talk, and I became expressionless, both physically and emotionally. I was very muted as a child. Now that I am a parent I have created a space for my kids to be who they are, unapologetically. That is its own healing, and I am proud of that because I think as an abuse survivor, unlearning what was modeled for you is a very hard thing to do. As a result, I like who my kids are. I learn from them. If they express themselves in a way that I don’t like, I use it as a chance to check myself and examine why I am reacting that way. I like that my kids can be human. I am proud of that, even when it’s frustrating and maddening.

What are you most proud of in your work? I am most proud of the fact that I just keep showing up, in spite of mental health challenges, in spite of motherhood challenges. As consuming as motherhood is, especially with special needs kids, I am really proud that I show up and allow art to hold me and hold everything that I carry every day. I am beyond grateful that I have it, because I don’t think that I would be able to be a good mom, a good person, a good activist, a good anything without it.

“What are the things that affirm who you are as a whole person? What helps you stay connected to yourself? How can you nurture those things that affirm your whole personhood?”

What advice do you have for other Mother Makers? Build as much of a supportive infrastructure as you can. I don’t mean just child care or having people around, but I’m talking about rituals and routines. What are the things that affirm who you are as a whole person? What helps you stay connected to yourself? How can you nurture those things that affirm your whole personhood? When you can nurture those things, that allows you to show up for yourself and for your creativity when you’re in the studio, or when you’re practicing. It also helps you silence that mom guilt that starts to yell: “You’re not spending enough time with your family!” And you say, No. I am. I am a good mom and they have everything they need.

Work with your ebbs and flows.There are different seasons. Some seasons you’re really productive, and some seasons you just need to hibernate. You also just need to live a little bit. You have to have seasons of living so that you can have more productive, creative seasons.