I was so excited to read your book. I related to it so much, in so many ways. First of all, I grew up in Madison, and you went to school in Madison. I went to school in Pittsburgh. You ended up in Pittsburgh. And more importantly, reading it made me feel like you were voicing all of the thoughts that I had in my pregnancy and in early motherhood. It’s amazing that you have this account of your story in such detail. How do you work, as a writer, to compile all of your thoughts and information to create a book like this? Are you just constantly journaling? That book was exceptional, because I’d done that before while traveling, taking lots of notes and things. But this book really grew out of the heat of the experience. I could never write it now, looking back. It was something that really had to come out of that particular moment. There’s something surreal about those early months. I was just sort of making sense of being in this liminal zone. It was the only thing I could think or write about.

I know some women who become mothers and don’t want anything to do with it in their creative work. For me, it was very much the opposite. My brain literally could not deal with anything else, and that was where I was going to direct all of my energy. Part of it was definitely things that I wrote down in my journal, and part of it was that I would have a writing spell where I would just get it all out, whatever was going on in my mind at the moment. Some people would tell me that I would need time to digest the experience before I wrote a book about it, and in my case I needed to write that book when I did. I needed to be in that experience to write it.

It was also so striking when I was pregnant. I remember just going to the bookstore and getting directed to the pregnancy/parenting section and feeling like there was nothing other than pink clipart of a baby on a parenting manual. I had to do so much digging to find the few literary books that exist on pregnancy. I couldn’t understand how that was possible, but the experience felt insane!

"Some people would tell me that I would need time to digest the experience before I wrote a book about it, and in my case I needed to write that book when I did. I needed to be in that experience to write it."

You had talked in your book about devouring work by other mother authors. What are some of your favorite things that you’ve read and connected with? The number one book came in right at a critical moment in my pregnancy when I had to tell myself, okay, I can do this. It’s going to be okay. That was Louise Erdich’s book The Blue Jay’s Dance. I loved it because it’s a very subtle book. My tendency as a reader and writer is to take a subtle everyday focus. I love language that brings out the everyday experience, and the kind of book where you close it and you feel your life in a different way. Dance was a beautiful example of that. I loved seeing Erdich’s intelligence at work in the context of pregnancy and motherhood. It was beautiful and compelling as a literary work, and the writing itself gave me relief. I realized that this is an area where I can use my skills, where I could use my brain. It was so redemptive in that way.

Then I read Anne Enright’s Making Babies, which I just loved, and it’s a little bit lighter. I just wanted something that captured the more ethereal, fleeting nuances of that particular moment and those particular transitions.

The poet Beth Ann Fennelly has a book called Great with Child, filled with letters that she wrote to a friend who was pregnant. That’s also really beautiful. And then there’s Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work, which got a lot of press because it’s a very unsparing look at some of the brutalities of the first years of motherhood. I was terrified a little to read it because I sort of intuited all of that already. I didn’t know if I needed it spelled out! But the writing was so compelling and it was totally worth it. It was good to position myself against that, and realize that’s not my experience. I consider myself someone like her, with an artistic and intellectual life, and thought I would be totally stifled by this, and I wasn’t. It was so inspiring and interesting to see that type of intelligence at work, considering breastfeeding and all of the everyday realities. The fact that it is so compelling and surprising seems a little bit sad to me.

As a writer, reading is the way that I make sense of things, so I needed to A) get into the depths of the experience, and B) have something show me that it was possible to write about motherhood.

Take us back to your childhood growing up in Ohio. How was writing a part of your life as a kid? I was always writing. That was very clearly my skillset. I knew I was not going to be a mathematician. I was very much in the art world from the beginning. I’ve always been more interested in nonfiction, and writing was my way of expressing these complicated ideas. Oh my god, some of the essays I wrote in high school, about things like A People’s History of the United States. Now when I do more journalistic writing, it comes out of that same impulse, which is probably horrifically righteous, and of course has been somewhat tamed down, thank goodness!

Back then, it was more about ideas, and that’s why I always thought I’d go into academia. I loved that play of ideas and the way I expressed that was in writing. Then I grew older and became more creative, and got more interested in the writing itself.

What did you study in undergrad at the University of Wisconsin-Madison? History of Science. I made a life out of choosing the most esoteric little pockets of impractical academic work. I did my undergrad in History of Science and then I went on and got an MFA. Kudos to my parents! My brother got degrees in theatre and jazz, so we’ve always been in this competition of who can choose the most impractical degrees! In theory it seemed like it could go somewhere!

What did you think you were going to do with your degrees? I thought I was going to get my PhD in history. I thought I would take some time off to travel, and that time off ended up being a decade of traveling. I graduated in 2004, and then I went back to grad school in 2010, but for an MFA, not for history. As time unfolded while I was living overseas and traveling it became clear to me that I wasn’t particularly interested in that. To be an academic, you really have to go down a rabbit hole of research in one area, and while I love reading and academic work, what I was really interested in was writing and translating that for a larger audience.

"I bought a one-way ticket to Peru, and wanted to see what I could do, how far I could go, and how long I could last."

What were you doing while you were traveling? Where did you go, and what were you exploring at that time? When I first left, I took a trip by myself to Mexico City. It was my senior year of college. I had lived in France, I had traveled a little bit in Europe, and I did a study abroad program, but that was the first time I really went by myself to somewhere that wasn’t Europe. I met all of these Europeans who were traveling for like, two years in Central America. So when I came back, I was like, I’m going to go traveling. This is a thing I’m going to do. So I just worked and saved up money and the goal was to test the limits of the possible.

I bought a one-way ticket to Peru, and wanted to see what I could do, how far I could go, and how long I could last. So I traveled for about eight months and then came back home and started this early 20s self discovery sort of thing. I wanted to see how far I could take the traveling. So I applied for a teaching assistant position on Reunion Island, which is a little island in the South Indian Sea, French territory, and I got it. So the first trip was very much a situation where I saved up money, and I camped on hostel roofs and somehow managed to live with a teeny tiny amount of money that I cannot even imagine today. And from then on I applied for teaching jobs that paid for the travel and allowed me to earn a basic living. That position was ridiculous. It was the French dream. I had a month of paid vacation and a seven month contract for 12 hours a week. So I just kept seeking those things out. From then on out it was teaching—teaching in Mexico, and then in China, then Japan. And it was on the pretext of how much I enjoyed the teaching, but while living there and continuing to have these little mini-lives in different places.

Were you teaching English? I was teaching English. In China I taught writing, basic composition. Everywhere else I taught English.

How long did you think the traveling lifestyle would last for you? I thought that would just be the way it would be. I didn’t see an end to it. When I was in it, I never saw it as a phase. I never saw myself settling down someday. I just thought that was the way I was going to live my life. I did want more of a career. By the time we got back from China, in 2008, I started thinking about applying for a PhD and pursuing writing. So I started to get a little more serious about that, and then I started to think about graduate programs. But when I was in graduate school, I was never thinking about how I could get a job and live and work in the US. It was very much all over the place.

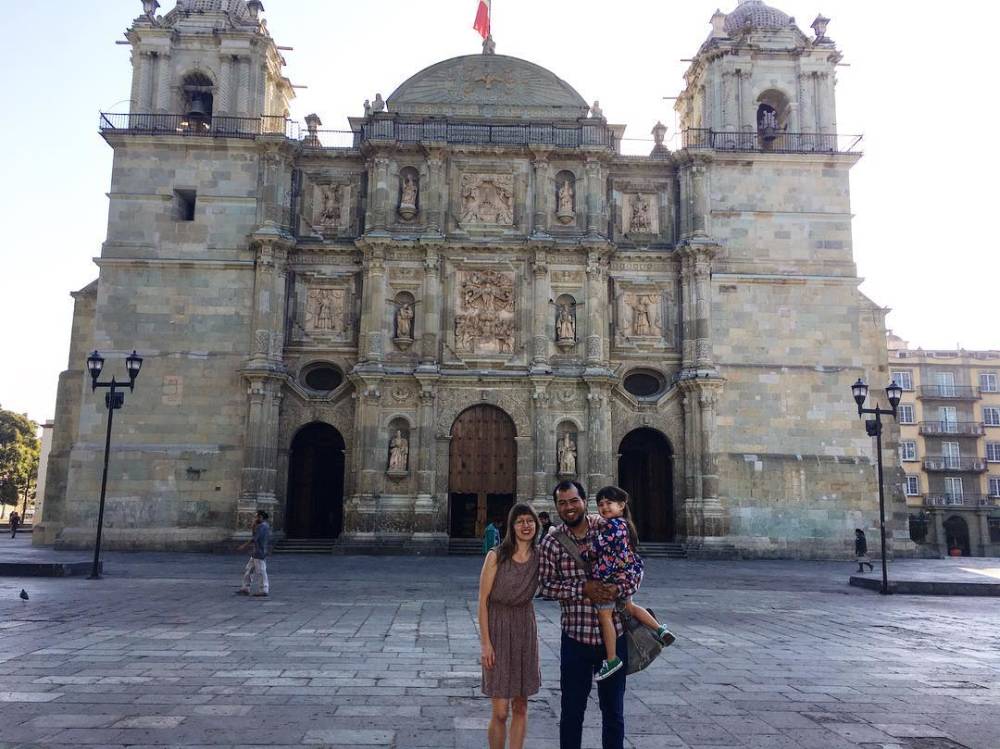

When did meet your husband Jorge? I met him in 2006 in Oaxaca. I had gone down there to teach a month-long intensive course. And then I got a job at a scrappy little language school and ended up staying. I met him at a cafe. It was one of those things where we met in the cheesiest possible way, where he was like, “What are you working on?” He still insists to this day that he was just fulfilling his role. He was temporarily managing that coffee shop, so he’s very insistent that he was just fulfilling his administrative duties as a manager. Then we hung out every night for a week, and I think I moved in two weeks later. It was just a done deal.

When did that urge to move back home start for you and what did that look like? I think when it initially started I was probably in graduate school, and it was something I had to back into without acknowledging it. I really love being near my parents, but it was just an accident of funding, really. I got full funding at Pitt, so it was very clear that I would go there. I ended up two hours from my parents’ farm, and I loved it so much that once the program was finished, we didn’t just high-tail it somewhere else. It wasn’t necessarily a conscious decision to stay near family; it was more like, what are we going to do? And then my dad offered us his cabin, so we moved in.

Then I got pregnant, and that was really when I realized I didn’t want to go anywhere. It just tied into this understanding I started to have that who I am as a person and the way I see the world is rooted in this particular place. And that I will always have a certain affinity for that, and my aesthetic and my perspective is very tied to that. I became more interested in embracing and acknowledging that after assuming for a decade that none of it mattered. I could totally reinvent myself.

When you were there, you kind of just felt more settled. Yeah, and like I said, there was this emerging pattern where I was becoming more interested in what it meant to have a more settled life that didn’t necessarily mean committing to one place for 20 years, but for me, meant not always searching for the next thing. Where everything is so temporary, a novel experience, and then I move on to the next experience. And also because I had happened to be so close to where I grew up, I just got more interested in seeing that again. Really paying attention to that, in a way that I had assumed for so long that it was uninteresting, and I wasn’t going to notice anything there. And then as I was literally pregnant and in this cabin for nine months, it was like, well, there’s nothing else to look at, so let’s look at Ohio.

I think a lot of creative people kind of live like that, just kind of hanging on and grabbing for any next opportunity that comes along. But that decision to stay put can feel so comforting. Yeah, and I think that really deepened my work. Not having something external to always aspire to forced me to go deeper with my work and to contend with some different questions.

What were you doing for money while you were living there? We were living off of Jorge’s salary. I was doing some freelance work, here and there, that brought in a little bit. But basically we weren't paying rent. We lived in the countryside. Never went out anywhere, especially compared to our life now. Look at our life in Pittsburgh today. We go to the coffee shop all the time. We go to restaurants. And we did none of that back then. We were literally just in the cabin all day. Or hanging out with my parents, or hiking. So we had basically no expenses, but also Jorge was doing weddings in Pittsburgh a lot at that time, and then we went to Oaxaca for several months, and he was doing weddings down there, so that allowed us to sort of squeak by. And that last summer, too, when I was done with graduate school, I still had a stipend and he had worked weddings all summer, so we had saved up a little bit of money. But I mean, it was very minimal, and we were sort of able to squeak by on that.

Just thinking of all the things when you have a baby that you think you need. I’m sure if you’re living in a cabin, you realize you don’t need as much as the rest of us think we do. Yeah, we went back there maybe a year ago, and we hadn’t been there in awhile, and I was like, oh my god. I cannot believe we lived here. It’s tiny! It’s a little tiny cabin. It’s extremely rustic. At the time, it did not feel weird to me at all. It seemed like as good a place as any. Now we have a house in Pittsburgh, and we have a much more conventional life—it’s so different. Obviously we were going to have to do something after our daughter was born. We weren’t going to live there for the next 10 years, but we aren’t the kind of people who thought much about that, beyond immediate plans.

What were some of your expectations of how you were going to feel as a mother once your daughter was born? I think this is fascinating and something I would like to write about a lot more. It’s not like I ever planned on not having kids, I was never one of those people who knew from a really young age that I wasn’t going to have children. But I was never particularly interested in it either. Once I met Jorge and I started to get a little bit older, I began thinking I could have one kid. That might be a possibility. But I had always assumed that when I did have a kid, I would be able to keep it in it’s own space where it belongs. Not literally, but it’ll be in this realm, and I’ll have my career and my life and all of this stuff that I’ve built up as the important stuff. I’ll have that, and I won’t be one of those women who’s totally absorbed by my child.

"…motherhood is one of those transitions that really tests your idea of who you are."

It was a weird point of pride I think, and the whole logic seems so strange and a little bit sad to me now. Now I hear from women that they’re completely shocked at the complexity of motherhood or the realities of motherhood. Not referring to so many diapers, but how it’s actually a really intense, complicated, personal change. And I think that speaks to how little attention we pay to motherhood culturally, beyond the sort of sentimentalized stuff that you can find everywhere. I had really thought that I would make this transition and have this baby and go back to work and that’ll be that. And maybe some women totally do that, but motherhood is one of those transitions that really tests your idea of who you are. All I really wanted to do was be with my daughter, and my entire life philosophy shifted dramatically. I wasn’t even interested in the same questions that I was interested in before. Nothing had any bearing anymore in the same way it had before I was pregnant. All of those things—my work and my projects—just so completely lost their relevance, and it was like starting anew.

And now, let’s talk about when your daughter was born. What were the logistics of you getting the time and space to write in that tiny cabin? In some ways that feels like it was such a luxurious time, just because she was born in the summer and Jorge was working a lot. That was good because it’s how we were maintaining our lives. I didn’t have any plans to work. I wasn’t stressed out. I just thought I would do this thing and make it work for the time being.

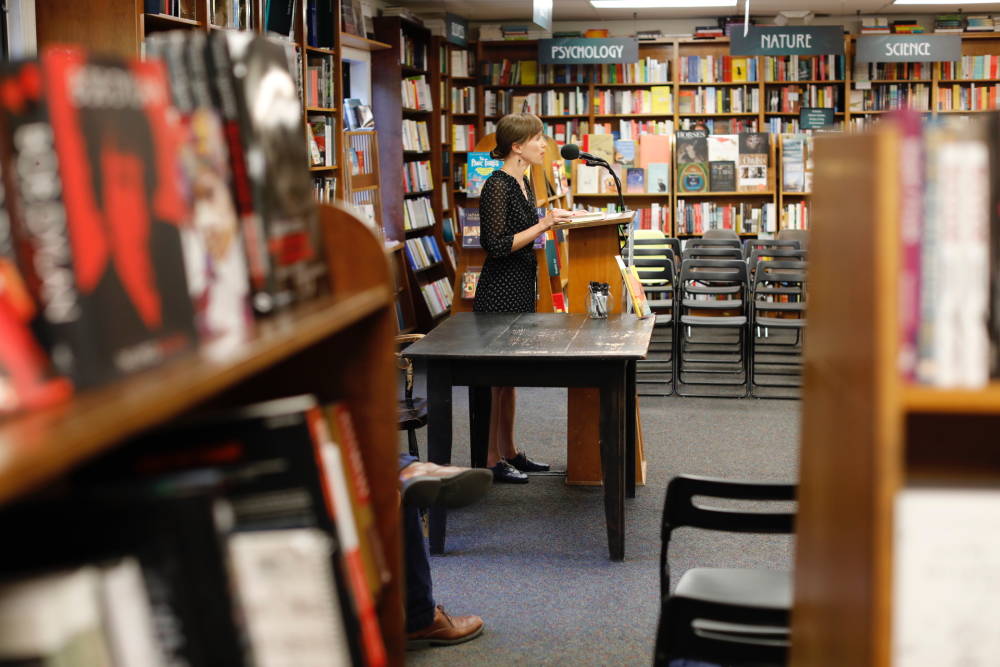

For a writer or an artist, that’s a wonderful way to approach work, because you just don’t care. If I have the time, I’m going to write about what I really need to write about, or what’s fascinating to me. I’m not thinking about it in terms of publication or success or trajectory. That’s part of where the book came from. Also, I had a little bit of a “screw it” attitude towards publishing. I didn’t care. I was going to write what I wanted to write, and I had had enough experiences with success, rejection, success, rejection. I grabbed the time where I could, and Jorge would take her for a few hours, and my parents would take her for an hour or two, and I would write. It was not like it is now, where it’s a constant juggling act!

What does it look like now? Now, she’s in preschool, so I have a “day,” which is really surreal. She’s gone from eight or eight-thirty until three, Monday through Friday. We kind of went from zero to a full day, and I was really worried about that, but she did fine. Now I have a work day, but it feels way more stressful because I have to make it incredibly productive. It has to be real work that is aimed at something. It’s a different rubric to work under. I’ve also really underestimated the intensity of the working mom chaos and making that shift every day at three o’clock from being in writer world to mom world. I totally underestimated how jarring that would be.

When did you move out of the cabin? I got a Fulbright in 2015, so we went to Mexico for that whole year, and when we moved back we chose Pittsburgh because Jorge’s photography business is here. It was the most viable option for where I could write and we could have a decent lifestyle.

So your daughter’s a really good traveler, then? She is a really good traveler! She’s just like, now we’re on a plane, now we’re like in a taxi, now we’re at this giant fiesta and people are throwing candy everywhere and now we’re sleeping on this mattress. She’s really, really good.

How does it feel for you to be doing what you love in front of your daughter? Yeah, that’s complicated. I want her to grow up with this sense of possibility that you don’t have to adhere to a rigid societal track. You don’t have to conform to these certain expectations. At the same time, I’ve heard so many stories of women who feel pressure to set a standard for their daughters, and the kid walks away with the opposite thing. I feel wary of trying to project anything onto her in terms of life goals or what her life should look like. Both Jorge and I joke that we’re living under the Mexican model where she’s got to take care of us when we’re old. She’s got to be an accountant or something practical, so we have to keep her out of arts classes, for god’s sake!

What’s more important to me is that she feels at home in the world, in the sense that it’s not weird for her to get on a plane and go to Mexico. That she feels really comfortable in her life, going out and trying new things. I don’t want her to get sucked into this really narrow life where that feels crazy or exotic. Maybe that is part of being an artist, a little less conventional. But it’s more about the sort of priorities and perspective I want her to have on life. I want her to have a fluid sense of what’s possible, what her community is, and what’s “normal.” I want her to know that she can live her life in all sorts of ways, and be spontaneous and creative.

What are you working on now? I’m working on my second book, also at Pantheon, which is very exciting. It’s about the dark side of motherhood, the things we never really talk about, in terms of the psychological and emotional depths of early motherhood. There is an element of grief and loss and fear, and all of those dark, haunting things that we tend to keep out when we’re telling our motherhood stories. I’m looking at it from a lot of angles, covering the stories of a group of women. I’ll tell each story in detail, and interwoven with that will be a lot of research into anxiety, our cultural relationship to risk, and the neurobiology of the maternal brain. I’m looking at our normative understandings of that period, versus what’s actually going on biologically.

It’s fascinating, because we know so much—to almost an absurd level of detail—of what’s going on with the developing fetus. And we know almost nothing about what happens to the mother’s brain. I want to look at how that makes a significant number of women vulnerable to mental illness, and also grief and fear. I think it’s really surprising how much research has been done on the baby, and how little has been done on the mother.

"I would say to the women who are on the fence or worried about being marginalized because of motherhood to try to shut down the standard, very male paradigm that defines what is intellectually or artistically relevant."

What advice do you have for other Mother Makers? This is probably very specific to me, but some women don’t want to engage artistically with motherhood. I totally understand that. I would say to the women who are on the fence or worried about being marginalized because of motherhood to try to shut down the standard, very male paradigm that defines what is intellectually or artistically relevant. If you want to focus on motherhood in your creative work, do it. Shed light on that. Find your own consciousness there. That was part of my journey, being able to say that I would occupy this space, and own occupying this space. I think it’s really empowering when women decide to do that. And if you don’t want to do that, by all means, don’t. But my advice to people who are hesitant is to embrace motherhood, and see it as artistically valid and interesting.